|

Digital prostate exam

Because most neoplasms start in the peripheral zone of the prostate, they are often palpable. The digital examination is performed using an anesthetic gel with the urologist's index finger from the rectum. The doctor assesses the size of the prostate and the presence or not of suspicious dural or subdural areas. Even if something is palpated, it is not binding that it is cancer, but it can be, for example, a focus of chronic granulomatous inflammation and prostatitis. Conversely, even if the digital exam has no pathological findings and the prostate is soft, this does not rule out the presence of cancer. Generally, the decision to biopsy or follow-up will be made by your urologist after an extensive evaluation of the findings.

Prostate cancer symptoms

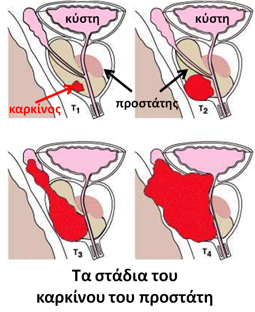

In the early stages, the disease does not usually cause symptoms. When the neoplasm expands, it can cause nocturia, decreased urinary frequency, urinary frequency, urinary retention, hematuria, bone spurs, and neurological symptoms from spinal cord compression due to bone metastases.

My urologist suggested a prostate biopsy. How is it done, what preparation is needed and what are the possible complications?

Prostate biopsy is the only way to confirm or rule out prostate cancer in men with suspected disease. It is a special invasive procedure that is guided by the rectal ultrasound, i.e. through the rectum, which is the final part of the large intestine. For extensive details related to biopsy, visit the 'prostate biopsy' chapter.

My biopsy showed that I have prostate cancer. What are the next steps and treatment options?

The urologist will explain the results and the degree of risk of the disease. You will probably be asked for the following tests:

1. Abdominal CT scan, to rule out lymph node and other metastases, for example in the liver.

2. Bone scintigraphy to rule out bone metastases.

3. Multiparametric MRI of the prostate, if available in your area. It is a modern examination that gives a very good picture of the local extension of the disease (possible extraprostatic extension or infiltration of neighboring organs). This can help in planning treatment (for example whether an attempt can be made to preserve the erectile neurovascular bundles to reduce the chances of erectile dysfunction after surgery).

Then and depending on the staging results, the urologist will explain the treatment options.

I have non-metastatic prostate cancer. What are the possible treatments?

When prostate cancer is localized there are three main options: radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy (external or brachytherapy) and active surveillance in low-risk disease.

Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy involves the complete removal of the prostate gland and seminal vesicles along with parts of the surrounding tissues, so that there are as negative surgical margins as possible even if the disease has microscopic periprostatic extension. It may or may not be combined with extensive removal of iliac lymph nodes, depending on the severity of the disease (lymph node cleansing).

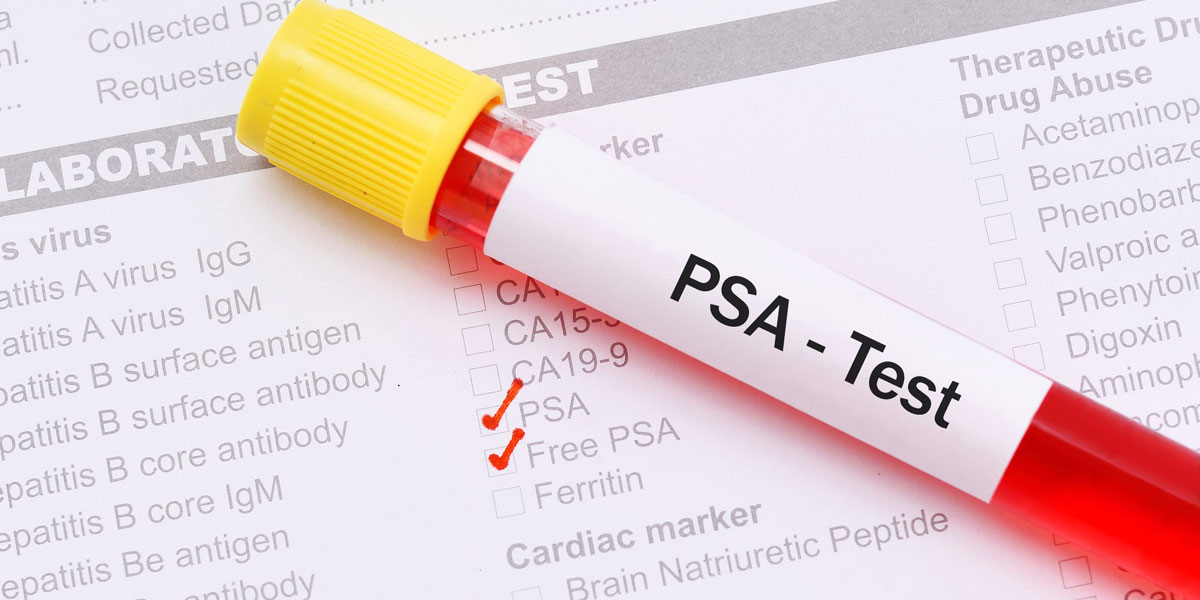

After the removal of the prostate and the seminal vesicles, the urethra is reunited with sutures to the neck of the bladder and a catheter is placed, which depending on the tactics of each urologist can remain from 7 to 15 days. Hospitalization days in open radical prostatectomy are usually 5-10. We ask for a PSA measurement 6-8 weeks after prostatectomy and this is usually close to zero. After surgery and depending on the final biopsy, follow-up with PSA measurements will be required, as unfortunately one in three men will have a biochemical relapse in the next 15 years (ie a PSA rise above 0.2 ng/ml without symptoms). In this case we usually do additional radiation therapy.

In the last decade, laparoscopic and robotic radical prostatectomy have been added to our options. Both appear to have similar oncological outcomes. Robotic radical prostatectomy with the DaVinci system is very popular worldwide today. It appears to offer, on average, fewer hospital days, less intraoperative bleeding, and a faster return for the man to his usual activity. Of course, as in all surgical techniques, the experience of the surgeon is very decisive.

Today, radical prostatectomy is the most popular treatment for locally localized prostate cancer in men with at least a ten-year life expectancy. Her oncological results are excellent and the majority of these men will live and have another cause of death in the end. Nevertheless, it is a major operation with possible immediate and distant complications, of which the man must always be informed.

Epigrammatically, the most frequent are:

Urinary incontinence: Usually soon after the catheter is removed most men experience urinary incontinence. The main reason for incontinence is that one of the two urethral sphincters must be surgically removed as part of the operation. We suggest a series of pelvic floor exercises to train the muscles of the area for the first year. Medication may also be prescribed if incontinence is severe. Finally, one year after surgery, the percentage of men who will still have involuntary loss of urine is around 10%. In this case and if the symptom creates a major problem in the quality of life, the possibility of placing an artificial clamp can be discussed.

Erectile Dysfunction: Unfortunately during radical prostatectomy there is damage to the erectile nerve bundle that runs right next to the prostate. In recent years and when the disease is of low risk, we attempt the neuroprotective method, i.e. the attempt to surgically preserve the nerves. This increases the likelihood of a gradual improvement in the erection in the first year. In general, however, the majority of men will have erectile dysfunction postoperatively and will not be able to achieve a penetrable erection without medication. A common practice, especially in younger men, is postoperatively to administer some of the erection drugs to improve blood circulation in the penis and, if possible, partially restore nocturnal erections. This protects the erectile tissue from neuroapraxia. If the months go by and the drugs don't work, we use the intracranial injections. In other words, we teach the man who wishes to give himself a fine injection into the penis containing a vasoactive substance, usually alprostadil. This results in a penetrable erection that usually subsides within two hours. Complications of the injections can be pain, small penile hematomas and priapism, i.e. a prolonged painful erection that must be corrected by the doctor immediately. If the man does not wish to try intracavitary injections, there can be a discussion about placing a penile prosthesis, that is, a device that is implanted inside the penis and through a special pump can be inflated and deflated according to the patient's wishes.

Cystourethral anastomosis stricture: This usually occurs within the first 12 months due to scar tissue development in 5-10%. This percentage appears to be smaller in robotics. It manifests itself with the appearance of significant difficulty urinating and prolonged urination time. If you notice this after surgery, inform your urologist. Transurethral dilation is usually required, but in a high percentage it can recur.

Lymphedema: More and more men with intermediate- or high-risk disease are performing extensive lymph node dissection. This appears to improve oncological outcomes over time. Also, it may be seen in the final biopsy that some lymph nodes are infiltrated by the neoplasm and this was not seen in the initial CT scan. Due to the lymph node cleansing, a part of the lymph drainage is fatally cut off and it takes time for a new network to be created. Thus there may be lymphedema, i.e. soft swelling in the scrotum and usually in the lower extremities. It is usually treated with special socks and repositioning of the feet. There may also be prolonged lymphorrhage from the drainage of the surgery and it may be required to stay for more days.

Radiotherapy

External beam radiation therapy is another non-surgical option for locally localized disease. Today with the most modern radiation therapy machines and the advancement of technology, it is possible to better focus the dose only on the target organs and limit the spread of radiation to the surrounding organs, thus limiting complications. There are large studies with many years of follow-up that show very good long-term oncological outcomes. Depending on the aggressiveness of the disease, the patient is designed by the radiation therapist using a CT scanner so that the areas to be irradiated are clear. If the disease is of high risk, the iliac lymph nodes are also extensively irradiated. Prostate radiation therapy is usually combined with hormone therapy, which is an injection given once a month or three months. In moderate-risk disease, hormone therapy is given for 12-18 months, while for high-risk disease, 3 years of hormone therapy is required. This is shown by large studies to have a better oncological outcome. Complications of radiation therapy are radiation cystitis and enteritis that can manifest with hematuria and hematochezia long after radiation therapy, urethral strictures, impotence and death (0.8%). In relation to radical prostatectomy, there is a relative dichotomy as the studies that exist are heterogeneous and not completely comparable. In general, it seems that at older ages (over 70 years) the results are similar, while at younger ages it is more likely that radical prostatectomy has better long-term oncological results.

A special form of radiation therapy in low-risk disease is brachytherapy. It is a minimally invasive method, in which granules of radioactive material such as Iodine-125 are implanted into the prostate with special guidance, which irradiate the tissue for a long period of time (about 6 months). This avoids damage to surrounding organs, such as the bowel and bladder. Brachytherapy is not recommended for large prostates or extensive neoplasms or medium- and high-risk disease, or for men with severe lower urinary tract symptoms, mainly difficulty urinating. Hospitalization is usually one day. Brachytherapy can also be combined with external beam radiation therapy. Complications include worsening urination due to urethral swelling, impotence in 50% and hematuria.

Active surveillance

A significant percentage of men with low-risk disease will never be threatened by it. On the other hand, any treatment option chosen (surgery or radiation therapy) can have complications. Active surveillance means closely monitoring the low-risk disease so that if it is found to be becoming more aggressive down the road, then curative treatment can be given. This results in half and more men never needing to receive curative treatment. Active monitoring includes regular PSA measurement, digital examination, annual prostate biopsy usually and lastly alternatively biopsy with multiparametric prostate MRI. In older or younger men with serious health problems (for example, heart failure) who do not have a ten-year life expectancy, there is also the option of doing nothing about the disease but only monitoring (watchful waiting).

I underwent radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. What follow-up will I need next?

Your urologist will explain the results of the final biopsy, which is very important for planning follow-up. He will also monitor you over time regarding possible complications (erectile difficulty, incontinence, strictures). Generally 1.5 months after surgery you should have a PSA measurement which is usually close to zero. It is desirable to be less than 0.2 ng/ml. So be careful because after the surgery the normal values of the laboratories are not valid as before the treatment and it is a completely different case!

Depending on the biopsy, PSA measurements will be recommended at regular intervals. A common regimen in moderate-high-risk disease is quarterly for 2 years and then every six months. In general, if the PSA is zero along the way, there is no reason to repeat CT scans and scintigraphy, unless there are signs of clinical disease progression. Exceptions are very aggressive neoplasms with a Gleason Score of 9-10 that may progress without necessarily giving a significant rise in PSA.

I have metastatic prostate cancer. What are my options?

Before the discovery of PSA, almost all prostate cancers were discovered at an advanced stage. In the last 30 years fortunately things have changed and today only 5% of men will be diagnosed with metastases, mainly in the bones. In the last five years with the discovery of newer drugs the survival of these patients has improved significantly and from 2-3 years ten years ago it has reached 5 years on average.

In metastatic prostate cancer there is practically no radical treatment. Treatments aim to improve survival, treat symptoms, reduce disease complications and improve quality of life as much as possible.

The main treatment option is hormone therapy. Practically, it is a medical castration, in order to rapidly reduce the levels of testosterone, which is considered the 'food' of the cancer cell. In the past, orchiectomy was performed on both sides. Due to the serious psychological problems this created, its use has been greatly reduced. So today we use injections of LHRH analogues or antagonists. These are done monthly or quarterly depending on the content and active substance. In this way the PSA value drops significantly, as well as the testosterone value. This is how we put the cancer cells to sleep for a period that varies from 1-2 to much more years. Main complications of hormone therapy are erectile dysfunction and hot flashes.

The doctor will monitor you closely clinically and with PSA measurements. At some point the PSA usually starts to rise. This is due to the development of hormone-resistant cells and thus the disease jumps to the hormone-resistant stage. When the PSA increases, the value of testosterone must first be measured to see if it really is low and at castration levels, because the increase can also be due to the injection simply not doing its job perfectly. When hormone resistance is confirmed, we proceed to second-line hormonal manipulations (for example, adding or withdrawing an antiandrogen).

Today we have in our hands two excellent antineoplastic drugs that the man takes at home. It is enzalutamide and abiraterone that revolutionized modern oncology of the urinary system. A large proportion of men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer will respond clinically and with a fall in PSA and live for several years. These drugs are very expensive, but they are fully covered by the insurance funds through a procedure carried out through the EOPYY. There is also the option of chemotherapy with taxanes. This was the classic treatment of hormone-resistant disease before newer drugs were discovered and released in the last 5 years.

Another important risk for men with bone metastases is the risk of pathological fractures. For this reason, every month we inject a special substance that helps a lot by reducing the possibility of fractures. This injection is fully covered by the funds and the insured obtains it through a special procedure at the EOPYY offices.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men after the age of 50. Today we have excellent modern options in our arsenal and oncological outcomes are very good, even in advanced disease. Early diagnosis is important, especially in high-risk men. Do not hesitate to visit your urologist.

|